About those scales. My piano teacher said something useful (she often does). She said, “I don’t pay any attention to black or white notes, because they are all the same.”

“Duh?” I said, a frequent response in my adult piano lessons. “They look plenty different to me! White ones, and stubby black ones that stick up—what could be MORE different than that?”

So I thought about it a while. I thought about the top of the keyboard, where it’s closest to the soundboard. I noticed that at the top the keys were exactly the same width and distance apart and there were, by golly, twelve of them in a row that fit within an octave. Once you see this, FORGET the black and white color scheme. Just imagine the keys are all pink and don’t stick up different amounts.

Now an interval of a major third is always the same stretch for your hand: five skinny pink notes. Stretch your hands to an octave, keep your hands stuck in the same exact shape, and play each of the twelve notes in turn. Twelve pink notes.

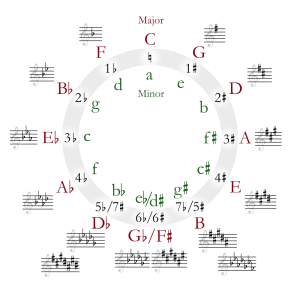

Now, think about the intervals between the notes of the major piano scales. No matter where you start, you play the pink keys 1, 3, 5, 6, 8, 10, 12, and 13. So, regardless of the key on which you start, if you can make your fingers feel the same pattern, you will play the major scale of the note you start on. If you start on A-flat (a VERY scary note), ignore the blackness and whiteness of keys, and have your fingers maintain the feeling of the distance between the notes (rather than trying to name the notes you play), you will autoMAGICALLY play the notorious scale of A-flat.

This is, in fact, one of the very clever things about pianos—hats off to whoever thought of it. Piano scales of eight notes (including the octave) always occupy the same width of piano, no matter where you start. A 7th is always the same spread. An octave, the same spread. The keys are always the same distance apart.

My father played in a dance band all his life. He could play anything he heard in any key you wanted, and if you watched his hands, it seemed to me that he knew what shape they needed to be. His hands were in that shape BEFORE they got to the keys. He played without looking and he would read music written in one key and play it in another key without thinking.

This is why I didn’t learn to play as a child. I thought that’s how it would work for me too. You sit down, and you play things. I was most put out to learn it took work.

The math of music is one of the things I find most interesting about the piano. A piano, musical notation, piano scales, chords, and so on are all amazing in the same ways that the chambered nautilus is. It’s not clear where the math ends and nature begins.

I think the order should be It should be 1, 3, 5, 6, 8, 10, 12 (, 1). If you play 5, 6, and 7 in a row, that’s three notes that are all a half step apart, which doesn’t happen in a major scale – though it would in a blues scale: 1, 4, 6, 7, 8, 11 (, 1).

Thank you, Ian, for reading and for pointing that out. You’re absolutely right, and we have fixed the numbers to make it accurate.

What a delightful non-pretentious read. Thank you mysterious ghost writer for this perspective.