Editor’s Note: We bring you “The Wurlitzer,” a literary short story by the award-winning writer Christi Craig, set to music performed by founding editor Nancy M. Williams. Christi occasionally dabbles on the keys and wants to sign up for adult piano lessons. She wrote this piece after discovering that the Wurlitzer her husband’s uncle gave her a few years ago would not stay tuned. Listen to the audio version here, or read the transcript below.

Story and voice: Christi Craig

Piano: Nancy M. Williams playing Andante from Schubert’s Sonata in A Major

Producer: Joanna Eng

Melvin Learner pulled up to 325 North Hockenberry Lane with the sole purpose of setting a Wurlitzer piano on a well-tuned path again. The combination of the winter chill and the clock reading ten minutes past his usual quitting time made him irritable. He’d just come from a house not five miles away and hadn’t had a chance to warm up in his car. Now, he was about to enter the house of a desperate woman, a last minute addition to his schedule.

Lenora Baker was in dire need of a tuner. She’d stretched out the word dire over the phone when she called two days ago, on Melvin’s forty-sixth birthday, just as he bit into a piece of carrot cake he had picked up at the PDQ. She had a piano, she said, inherited from an aunt, and the kids had been pounding on the piano for weeks, punching out sour notes and bitter tunes and driving her crazy. She loved her kids, she told him, and while she appreciated a little creative ingenuity, the sounds coming from that piano were just horrid.

That piano, she’d said. Horrid.

He started to ask a few questions about the instrument before he decided if and when, but Lenora Baker never gave him the chance. She rushed through her address and said she’d pay “whatever!” and begged him to stop by “A-SAP,” because of something about her kids being with their father. “And, they’ll be back soon,” she said. “Pounding away” and “God help me, that noise!”

“God help me,” Melvin whispered.

Lenora Baker talked too much; she was the kind of customer he would normally pass on to his colleague, Dave, because Dave was a conversationist. Dave could recite the history of every piano he ever worked on or sold, which he did all the while Melvin shared an office with him at Beethoven’s Haven. Dave never stopped talking. Not even when Melvin walked out the door after being “excused” for something related to customer service. Or the lack of it. Dave followed Melvin out and told him he should “lighten up, fella. You’re young yet.” To which Melvin responded that if age had anything to do with it, maybe they ought to send him packing. “Just like your wife sent you packing.”

That shut Dave up.

Considering his last words with Dave, Melvin knew it was up to him to save the piano from ruin. He agreed he’d stop by her house that Friday.

Lifting his bag from the back seat of his car, he walked slowly up the drive, his shoes pressing salt into the dusting of snow on the concrete. As the front door opened, his eyes fell onto bare feet, toenails painted a glaring shade of orange, and an ankle bracelet that jingled as the woman attached to them bounced. She waved the ends of a blue scarf she wore around her neck, then took hold of his arm, enveloping his wrist in a sea of blue cotton. He shivered.

“Mr. Learner!” she said, speaking with the same excitement he’d heard over the phone the day before. “Please! Please come in.” She pulled him inside and insisted that he call her Lenora, pointed to a mat and said, “For your shoes.”

“My shoes?” He stood frozen, one hand on his bag and the other on the small spiral notebook that held her address.

“Oh, yes,” she said, without further explanation. She waved for him to follow her, so that he was rushed in taking off his wingtips. He didn’t have time to slip the laces inside, didn’t have a second to pull up his socks that he now saw were sagging at the toes.

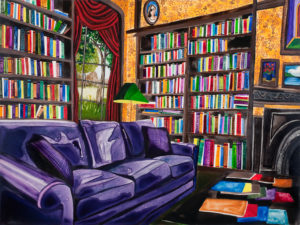

As she led him through the house, Melvin stepped over books and magazines that littered the living room, inched around shelves of toys and art supplies, and hesitated at the door of her bedroom, in which he saw the piano pressed up against the wall between two windows. An unusual place, she agreed, but it was the only space available for now. She hopped onto her bed, waving her scarf again, and told Melvin to make himself comfortable.

He stood in the doorway, shifting his weight from one foot to the other. He would have to step over a pair of black boots and, what appeared to be, a pair of unmentionables peeking out from under the bed. Hesitant to see what may be hiding on the other side, he slipped lightly around her bed and kept his eyes on the piano. When he sat down on the bench, it wobbled, missing a foot glide he suspected, so he ripped a few sheets of paper out of his notebook and folded them four times to make a fitting stop. He placed it under the troublesome leg, then sat down again and shimmied to settle the bench into the paper.

“Look at that!” Lenora said from behind him, clapping her hands.

“A simple adjustment.” Perspiration rose around the base of his collar. He was used to people watching him while he worked, but never from the comfort of their bed. He gripped the sides of the piano bench when she spoke again.

“I could take your coat.” Surely he’d be more comfortable working without it, she suggested, and she was the only one who ever complained about the heat in her house. The kids ran around in t-shirts and shorts half the time.

The kids. He wondered. He listened for extraneous noise in the house, as he slowly unbuttoned his coat, but heard none.

She must have registered his search. “They’re with their father for the next few days, which makes for a lonely weekend. But, which also means I could crank the heat. Hmm.” She unwrapped her scarf and stepped out into the hallway, taking his coat from him as she walked past. The house was silent for a minute until the furnace kicked in. Lenora returned, then, and began telling him about her two kids. Frankie and Frannie. She was always mixing up their names and they were constantly driving her crazy, like with the piano—bang bang bang—but then they’d go swelling her heart with something simple, like the brush of her daughter’s hand around her leg as she reached in to hug her mama. Or the quick, second glance she got from her son when she dropped him off at school, as he turned around to make sure she saw him wave goodbye. “So much love. When you least expect it.” She sighed. “Do you have kids?”

Melvin shook his head.

She went on, talking about how quiet it was without them here, and she was still getting used to being alone at times. Then her words spilled over into her own conversation about the weather and how thrilled she was not to have to shovel and that she hoped he didn’t slip on the driveway. Did he slip?

“No,” he said.

“Good.”

He heard her settle onto the bed again.

“Do you always work this late, by the way? Because, I felt bad about calling you over on a Friday night, but I was desperate. Still, it being a Friday, surely you have somewhere better to go.” Here she took a breath.

Melvin shook his head again, then opened his mouth to clarify that he meant, no, he didn’t always work so late. But, she went on talking, so he focused back on the piano. And, funny enough, after a bit of her idle chatter, her voice settled into a subtle tune and grew quite soothing. Her laugh sang out like a waltz. It wasn’t long before he forgot he was sitting in a bedroom, with a woman he hardly knew. He cleared his throat and asked her if she knew much about the piano.

“Not one iota.”

So, he told her: it was a Wurlitzer. He offered her a bit of history, as he opened the top and pulled out the door at the bottom.

* * * *

“Wurlitzer,” Lenora whispered, letting the word roll across her tongue. From her perspective on the bed, she could see that Melvin Learner was sincere about his work, and younger than she expected. Melvin had sounded like such a crotchety old name. She almost laughed out loud when she remembered the look on his face at the door as she told him to take off his shoes. But the way his hands handled piano parts with purpose and with care…. She thought it funny how his shoulders rose up each time he relayed some fact about the piano: the probable year—shrug, how a Wurlitzer is perfect for learning to play—shrug, that the case was in quite—shrug—good shape. He ran his fingers along the keys from the bass to treble end and back. She knew that at least, she told him, treble clef and bass. “And middle C.” He turned and smiled at her.

“Well, your middle C plays minor,” he lifted one shoulder, and she laughed.

“That about matches my life lately,” she said.

“What’s that?”

Nothing, she replied, and she offered to make him some coffee.

She overfilled the carafe and almost forgot to start the coffee maker, as she listened to Melvin in the other room, play a chord out of tune, again and again, raising the pitch by small degrees until it hummed. Even she, who barely knew much about pianos, could feel the air soften when the notes hit just right.

“It’s sounding beautiful,” she said to him from the kitchen.

“The Wurlitzer is a very cooperative instrument. It seems content to sit here in this room, even if it is a bit….” He wanted to say unorthodox, but he didn’t want to offend Lenora.

“You talk like it’s alive,” she said, as she walked back into the bedroom.

“Well, I do believe pianos carry with them a sort of … ethereal quality.”

“I see.” She handed him his coffee. Standing over the top, she peeked inside. “It looks more nuts and bolts to me.” She winked at him, but he didn’t respond. “Complicated, I assume?”

“The mechanics of pianos aren’t difficult to figure out, but it takes a certain finesse to make them sing.”

“Like women,” she said. She thought he blushed.

* * * *

Melvin stayed for two and a half hours, tightening strings and sipping coffee while Lenora engaged him in conversation. She danced around him and the piano after he rolled up his sleeves and started playing tunes to check the quality of sound. She said that her aunt had tried for years to convince her to take piano lessons, saying you never knew when those lessons would pay off. “But at thirty-eight,” she said, “I’m surely past my prime—”.

“No, no,” he said. His face turned beet red then.

He played a hint of a Billy Joel song, which she loved, she said, as she spun in a circle. She asked him his age, and he let it slip that he’d just celebrated a birthday, “If you call a lager and take-out in front of Law and Order ‘celebrating.’” He laughed then cleared his throat.

How had she done that? Gotten him to open up so much. He hadn’t spoken—really spoken—to anyone in days, weeks it seemed, since he lost his job and had to move home with his mother. Since his brother called him a louse for mooching off a seventy-year-old woman. Since he told his mother why he got fired and she patted his knee and said, “Well, you never were a people person.” He hadn’t missed conversation. Until now.

Lenora stood next to him and ran her fingers along the keys of the Wurlitzer, playing nonsensical music every few steps. She filled the room with a force that Melvin couldn’t ignore, and he found himself tapping his shoeless feet to the rhythm of her song.

0 Comments