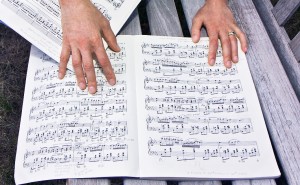

It goes without saying that to sight-read fluently and accurately, we must keep our eyes on the score. Looking down at our hands as we play breaks the continuity of reading, prevents us from looking ahead, and undermines concentration. Yet for many piano students, even some who have played for years, it is a frequent temptation.

We look down for different reasons. Sometimes there is a large leap that requires a legitimate glance at the keyboard (only with the eyes, not the entire head). But most often, we look at the keys because we feel insecure. We want to check if the notes we just played were the right ones, or we want to be sure that the notes we are about to play will be the right ones. So learning to keep our eyes on the score starts, first of all, with our willed intention to keep going, without looking down or back to check mistakes or doubtful readings. Next, it involves trusting that our hands, having spent many hours in contact with the keyboard, really do know how to find the notes without the help of our eyes. When I cover students’ hands with a notebook, they are often surprised to learn that they can in fact already sight-read without looking down.

Most of all, we need to develop an intimate tactile feeling for the geography of the keyboard, a sense sometimes described as having eyes in the hands. To some extent, this happens gradually by itself simply by studying repertoire and sight-reading regularly. However, we can acquire this ability more consciously by being aware of certain connections and sensations. A few examples from easy classics will show how this awareness can be learned even at the elementary level.

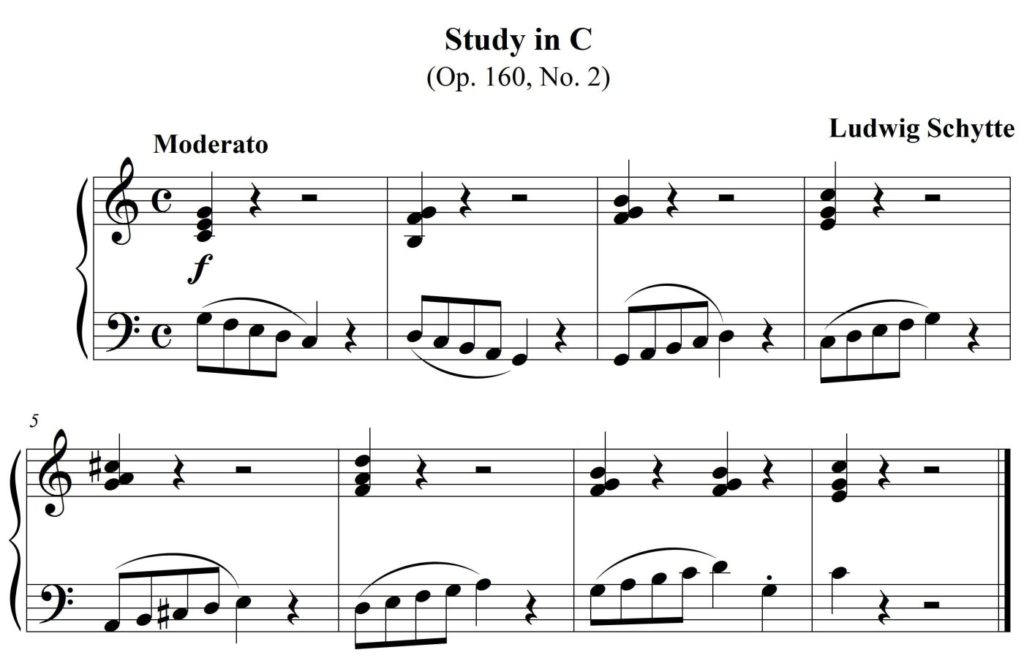

In shifts of hand position, it is tremendously helpful to look for the closest connections—common notes or closest notes. In the little Schytte study below, every chord in the right hand except one contains a G. Feeling this common tone as it moves from pinky to second finger to thumb and back to 2 makes it easy for students to find these chords without looking down. The rests provide ample time to look ahead, move the hand, touch the next chord, then play. In the beginning, it is helpful to draw lines between such common tones before playing.

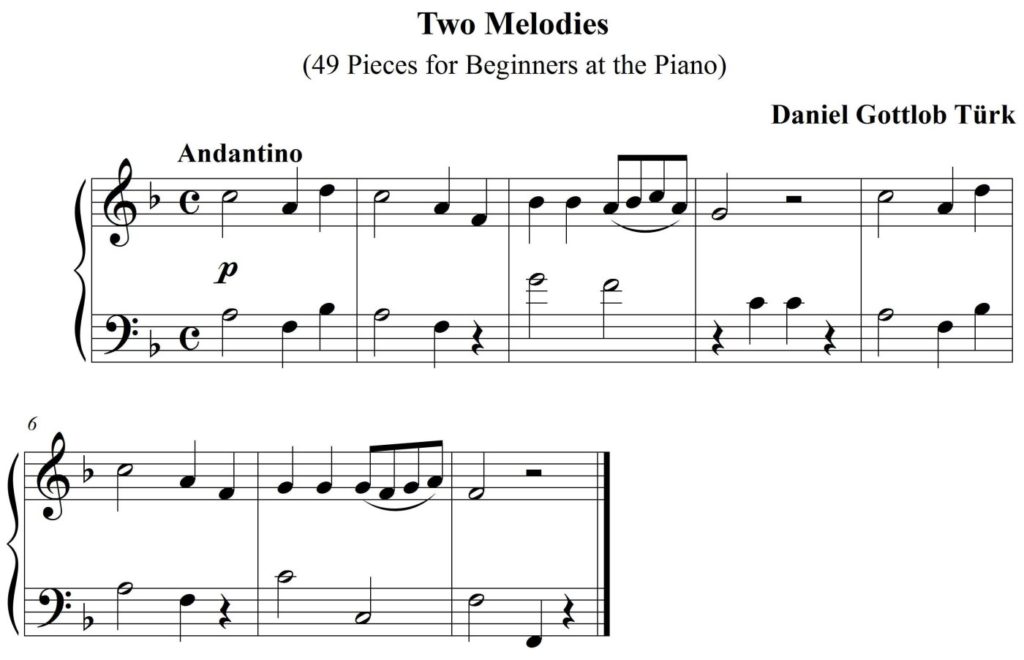

Sometimes the closest connection is in the other hand. In Türk’s Two Melodies, the left hand G in measure 3 is right next to the F the right hand just played. Moving back to the opening position in measure 5, it is the B-flat at the end of the bar we must feel with the fingertip, not the A. White notes all feel the same, and can only be found “blind” in relationship to the black notes. To find the octaves in the left hand at the end without looking down, students must first have memorized the shape of that interval in their hand. It’s a good idea to practice patterns like this, extended up and down the keyboard, before sight-reading the piece.

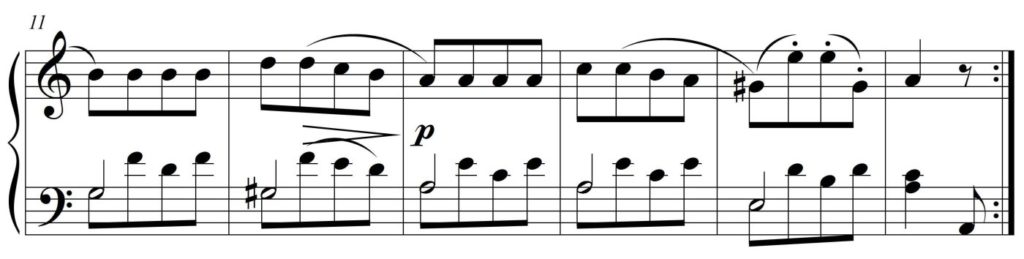

When there is no close connection, we can imagine one. The downward octave jump at the end of Czerny’s Russian Theme is a very common pattern, and one that causes most students to look down.

If we imagine an octave above the low A, we can feel an imaginary common tone from the previous dyad. Again, making up some exercises like the following before we play helps to ingrain the tactile sensation.

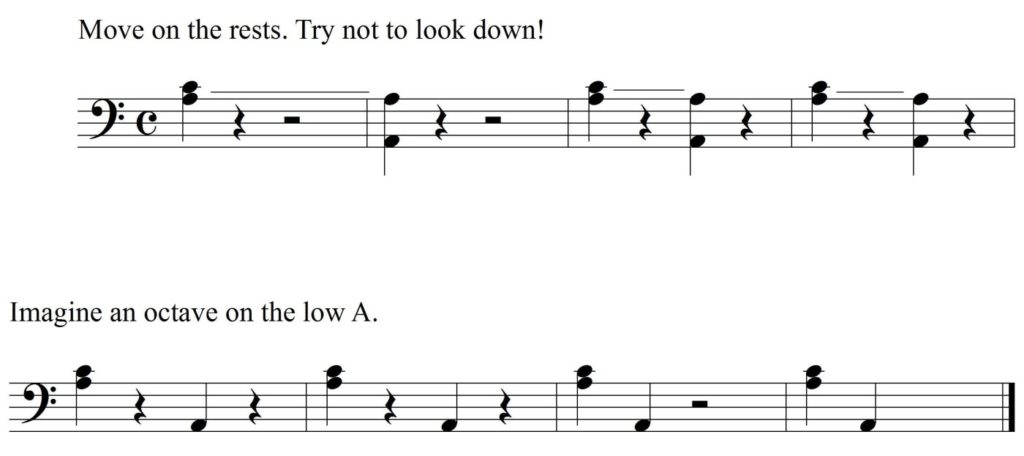

It may be argued that looking down once or twice in easy pieces like this doesn’t prevent a student from sight-reading in time. That may be so, but it’s at this stage that these tactile sensations are best developed, so that later on, in more difficult repertoire, the intimate knowledge of the keyboard is there when we need it. For teachers and advanced pianists, here is a Schubert Ecossaise to test your ability to see with your hands. Before you start, think about common notes, close notes, and imaginary octaves. Touching the keys silently before you play is also an excellent way to awaken the tactile sense.

If you wish, let us know how you did in the comment box below.

0 Comments