When I returned to the piano after a 25-year hiatus, I struggled with tempo rubato. I could not conceive how to inject my music with these mysterious elongations and compressions in the tempo. My piano teacher urged me to listen to classical piano music recordings, but unsure of exactly what to listen for, I neglected to follow his advice. I wish I had turned to Martha Argerich’s Chopin: Preludes and Sonata No. 2, my February Selection of the Month.

Translated from the Italian, the language of music, tempo rubato means stolen time. In the book Music Quickens Time, the pianist and conductor Daniel Barenboim advises that a piece played with tempo rubato should take about the same time as if no rubato were used at all. The pianist quickens the pace here, slows it there, to convey meaning and emotion. Through trial and error, I have discovered that tempo rubato happens naturally when I give myself permission to interpret the music and seek to communicate the feelings the music creates within.

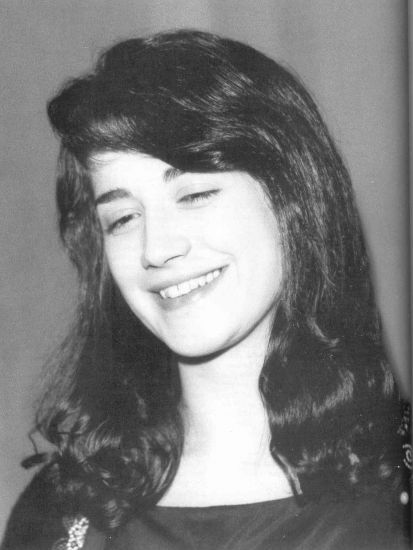

As my piano teacher suggested, listening to the greats can assist the amateur pianist and the student of adult piano lessons in assimilating tempo rubato. I find this particularly true of Martha Argerich, the Argentinean concert pianist whom Alex Ross says phrases so naturally that she embodies rather than interprets classical piano music. For some listeners, her use of tempo rubato is flagrant, even shocking, while for others it is stirring to the point of ennobling. I am fully in the second camp.

In Chopin: Preludes and Sonata No. 2, Argerich’s use of tempo rubato is instructive, surprising, and in the end, inspiring. Here are my comments on three of Argerich’s Chopin Preludes:

- In the Prelude in A-minor, the left hand swings like a woman with a heavy, careworn tread, while the right-hand melody is like a bard declaring the woman’s tale. The two hands have such different color that it seems as though Argerich is using two different instruments. When the left hand breaks off, and the right hand confides to us in a solo, I love Argerich’s hesitation before she plays middle C, an artful use of tempo rubato.

- The risk of the E-minor, one of the most well-known and oft-studied of the Preludes, is that the left hand accompaniment can sound repetitive, like an idle guitarist strumming chords. Argerich solves this problem by varying the intensity, first waxing, then waning, of not only the tempo but also the dynamics. She displays a dazzling use of rubato in the climatic forte section, where she speeds up the tempo to almost double that of the opening bars.

- The first time I heard Argerich play the Raindrop Prelude—elongating the melody with a studied beauty but then pulsing the A-flat accompaniment of the solo raindrops with a quick intensity—my mouth hung open with surprise. At that moment, some of the old strictures for playing classical piano music fell away. I realized how much liberty I could take with my interpretations.

0 Comments