Three weeks into Lent, I saw her slumped on a side staircase at Penn Station, her face set with weariness although she was fast asleep. Later that night, when I would practice Debussy’s Clair de Lune, the hopeful yet plaintive melody about moonlight, I would see the homeless woman inside the music.

Somewhat impulsively, in mid-February, I had decided to accept a challenge given by Rev. Michael Piazza, who writes the Liberating Word: rather than giving up a decadence such as chocolate for Lent, I would perform one act of justice each day.

On the very first day of Lent, as I hurried down Third Avenue in New York City, a man stood in front of a corner supermarket, his forehead creased as he yelled frantically to passersby, “Won’t you help me? I’m hungry!” Out of a timeworn habit, I pressed my briefcase against my body, lowered my gaze to the pigeons on the sidewalk, and quickened my pace.

What was I doing? The man had declared he was hungry, Lent had begun, and I owed Rev. Mike Piazza or perhaps even God or maybe just myself my daily act of justice. When I approached the man with money, his mouth hung open with astonishment, as though someone finally had heard his appeal. “Please use this for what you need,” I said. My body felt lighter when I crossed the intersection.

As Lent progressed, most days I managed to give help to someone who had less than I, sometimes as a formal donation to an organization, other times by handing out money or food on the street.

Then, walking down the stairs in Penn Station, I saw a young woman sprawled on the stairway, her head tilted on the riser above, her mouth hanging open in an oblivious sleep. She wore several layers of stained clothing, and I smelled decayed vegetables and urine, the familiar odor of the homeless. The light-brown skin on her face was unlined. She could not be more than 25.

At her youthfulness and exhaustion, a hopeless protest cried out inside of me. In a few minutes, my train was to depart the station. For what was I waiting? I fumbled with the zipper on my wallet. Underneath the sleeve of her coat, I gently slid some money. I felt my face open up with the hope that her life would get better. She did not awaken.

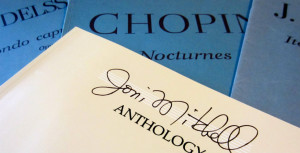

Later that evening, I practiced the piano. In Debussy’s Clair de Lune, I focused on the meditative, chiming opening, a series of thirds. I often found these thirds—really just small chords, two notes separated by a single key, so close to one another on the keyboard that they could be related—to be elusive. The difficulty was to distinguish the top melodic note from its cousin, hovering almost directly below.

Yet this time, I basked in the sweep of the thirds reaching up the keyboard, the translucent melody. Then inside the trembling thirds, I saw her, the homeless woman, sprawled asleep across the stairway. I shuddered. When she woke up, she would find the money and spend it on some necessity, but tomorrow her situation would be the same.

The thirds: together, this woman and I formed part of a small chord, not touching but nonetheless linked by our proximity in time and place. My decision to perform an act of justice every day was not a cute exercise that could expire on Easter morning. She was here, inside of my piano music, as a beacon for me to do more.

0 Comments