On New Year’s Eve in 1986, a crowd wearing pointed party hats pressed against the velvet ropes outside a Manhattan club. My boyfriend, Bob, charged up to the bouncer and whisked two tickets from the inner pocket of his tuxedo. Although we both were only six months out of college, Bob was a master at articulating his desires and executing his plans.

Inside the club, multicolored lights ricocheted off the fractured disco balls, while loud music throbbed, the thumping bass overpowering. I had no idea of the name or artist of this song. I thought about the people in party hats outside, hoping to score admission. I wanted to give one of them my ticket. This was not my music.

Since I had moved to Manhattan, I had seen a classical music performance only once, Leonard Bernstein conducting the New York Philharmonic at Avery Fisher Hall. Of course Bob had been the one to organize the event. In the later stages of his career, Mr. Bernstein conducted with wild gesticulations, occasionally jumping on his conductor’s podium.

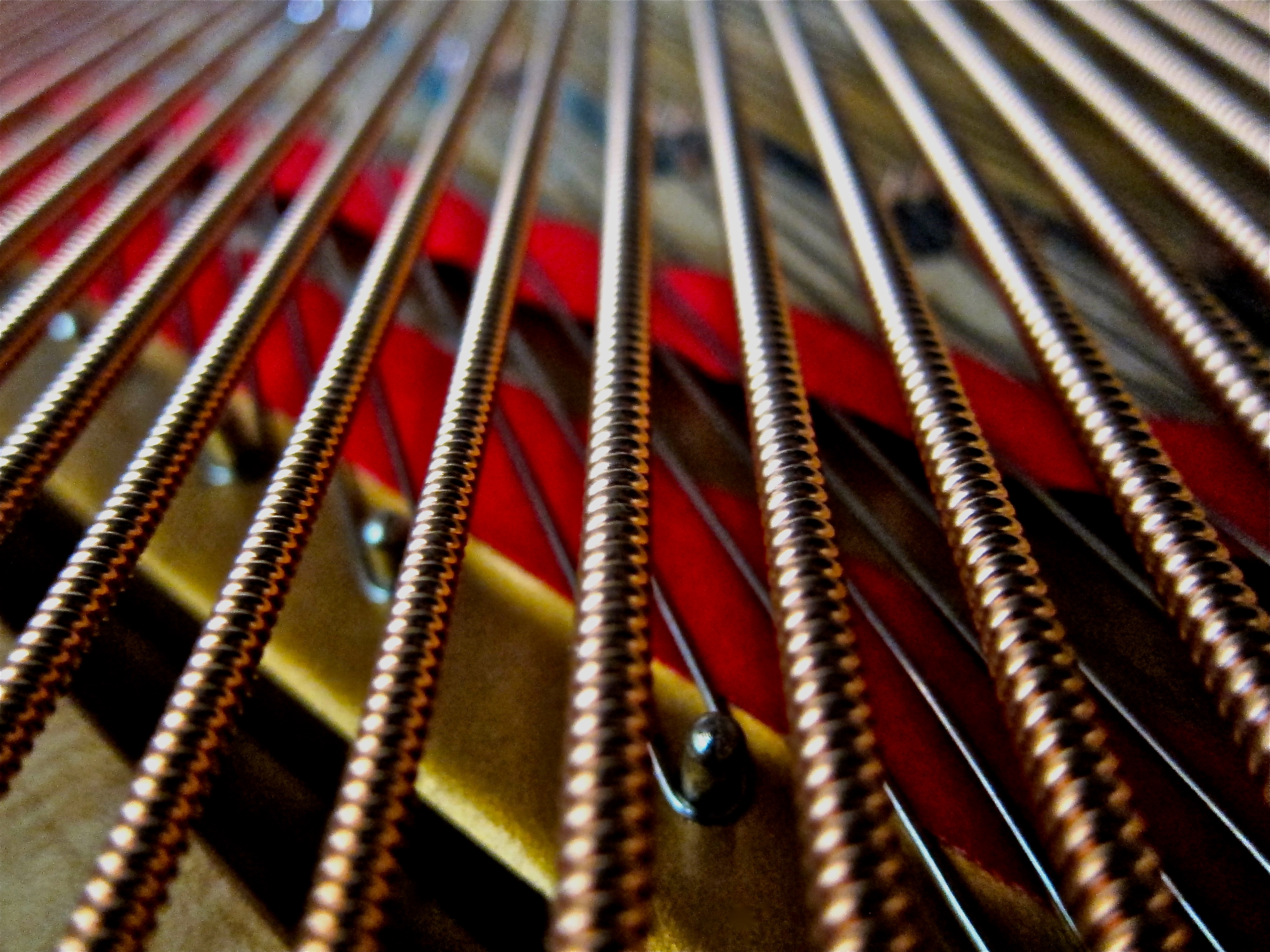

I focused on Mr. Bernstein’s body movements because to allow the music to permeate my senses would be to consider my former love affair with the piano, an affair that would connect to other beads on a troubling bracelet. The piano bench was the only place in my home where I had experienced an inner calm. I studied classical piano music avidly until the summer of my 16th birthday, when in the heat of their marital struggles which eventually would lead to divorce, my parents had pressured me to quit the piano.

I had sacrificed the music so that I would not lose my parents’ love. To reclaim the piano now would be to confront the essential horror I had ignored when I was 16: how casually my parents had treated something that formed a core part of my soul.

Not long after the concert at Avery Fisher Hall, Bob and I stopped by a brownstone on the Upper West Side, where our friend, Clifford, lived with his parents. In a long, narrow living room, under the glow of the lamplight, Clifford’s parents sat angled towards one another, reading. Behind them stretched a wall of ebony bookcases stuffed with old volumes. In the room’s rear waited a small grand piano, sheet music propped on the music stand.

Overcome by the tranquility, I stuttered when I told Clifford’s parents it was nice to meet them. Bob and Clifford headed to the door, but I lingered, my gaze drinking in the room. Clifford’s father looked at me over his reading glasses curiously. “Nice to meet you,” he had said again.

Now in the swanky Manhattan club, in between the interstices of air shattered by the relentless bass, I wondered what sort of resolutions I might make for the New Year. That existence Clifford’s parents led in the brownstone—the books, the piano, the companionship—was the life I wanted. What plans had I made, what steps had I taken to seek that life?

Six months later, Bob, disgusted by my lackadaisical attitude, among other faults, broke up with me. I moved to San Francisco, where I met the man who became my David. Twenty years later, when David enrolled in father-son piano lessons with our four-year-old, I found my way back to the piano. I realized I had to accept personal responsibility for shirking the painful truths about my parents and allowing the piano to lie fallow for so long.

Sometimes the longest journeys are the wanderings back to ourselves.

This is heart-breaking. Still, so glad to hear you found your way back to music. Good luck and enjoy.

Thank you, Evelyn. I am so grateful to have the piano back in my life.

While I would have loved the pulsing music on NYE in that Manhattan club, I also would have lost myself in Clifford’s parents’ living room, as you did. I’m glad that moment helped you find your way back to the piano and classical music, and sharing both with the rest of us!

Thanks for writing, Graham, and I’m glad you enjoyed the essay!

Looking forward to learning more about your journey!

Great to have you on the site, Valerie!