Erik Satie’s Gymnopédie No. 3 has enjoyed great popularity since Satie first published it in 1888. The music’s melancholy lyricism, warm harmonies and relative technical ease account for its popularity. Yet it’s not an unchallenging piece to learn. It offers an amateur pianist ample opportunity to hone aspects of their technique in order to play the music with sophistication and refinement.

Creating and Controlling Your Sound in the the Gymnopédie No. 3

Whenever I play the Gymnopédie No. 3, I feel myself passing by small islands of intense color, framed and hung on the white walls of an urban art museum. The Gymnopédie No. 3 requires the pianist to produce and control the subtlest nuances of volume and color at the piano. Though the overall dynamic range of the piece is narrow (piano to pianissimo), within this range Satie asks for a wide spectrum of dynamic contrasts, much like a painter needs to mix and contrast colors on a canvas.

The Gymnopédie No. 3 opens with a dynamic marking of piano. When the melody begins in the right hand in measure 5, Satie marks a very elongated crescendo that lasts for over two measures, until he marks a decrescendo for the right hand at the beginning of measure 8. Another example: in measure 15 Satie asks for elongated crescendo to the end of measure 16, in the middle of which, he then marks an equally elongated decrescendo that lasts for a full three measures. The fact that these crescendos and decrescendos are so elongated means that you have to slowly and subtly arch the volume of your sound, getting slowly louder or quieter. And I think the most difficult to achieve is the end of a decrescendo, where the sound must be minute and yet audible, like the faint glow of a fire seen through a house’s window in the night.

Perhaps this dynamics challenge in the Gymnopédie No. 3 is most difficult in measure 21—for me, the most poignant part of the piece, where the melody seems to express being resigned to sadness. Here Satie has marked the dynamics pianissimo, and then in measure 22 marked a small crescendo, followed in measure 23 by an elongated decrescendo that goes all the way to the end of measure 26, where the melody ends.

Perhaps this dynamics challenge in the Gymnopédie No. 3 is most difficult in measure 21—for me, the most poignant part of the piece, where the melody seems to express being resigned to sadness. Here Satie has marked the dynamics pianissimo, and then in measure 22 marked a small crescendo, followed in measure 23 by an elongated decrescendo that goes all the way to the end of measure 26, where the melody ends.

It should be noted that all of the crescendos and decrescendos Satie marks in the piece are exclusively for the right hand. So that means that as you work through the piece molding and coloring the sound of your right hand melody, you must first find just the right color and version of piano or pianissimo for the left hand—a sound that is beautiful and lends support to the melody without intruding upon it.

A Fast But Controlled Left Hand

In addition to controlling the left hand’s volume and color, the Gymnopédie No. 3 also requires the left hand to develop a dancer’s choreographic ability. The left hand must leap from the first beat note that begins each measure, up to the three- or four-voice chord that comes on the second beat—usually lying an octave or more apart. These first two beats in the left hand form the steady rhythm that underpins the entire piece and gives it its lilting quality. As such, you must become very adept at making these leaps confidently, quickly, and delicately. I suggest lots of slow practice with the left hand alone, working to get the sound just right, and only then bringing the music up to tempo.

Jean Yves Thibaudet and Aldo Ciccolini Play Gymnopédie No. 3

Although the Gymnopédie No. 3 has been recorded many times, I especially admire the recordings of Jean-Yves Thibaudet and Aldo Ciccolini. Thibaudet’s recording (above) is especially lean and clear, almost to the point of being sparse. His pedaling is extremely judicious, and his tempo quite slow. This, however, lets Thibaudet precisely capture Satie’s many elongated crescendos and decrescendos. Ciccolini’s rendition (below) of the Gymnopédie No. 3 is, by comparison, quite fast. He also makes great use of rubato in such a way as to almost imitate human speech, slowing down to really emphasize tender moments and then speeding up as the familiar main theme returns.

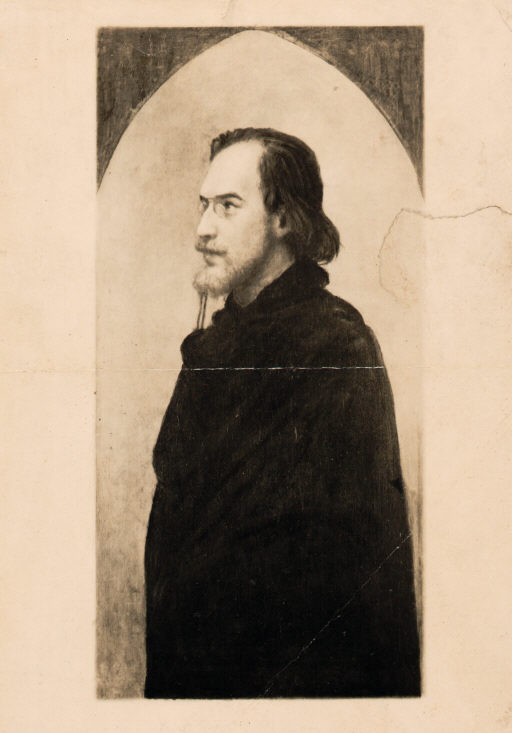

Le Chat Noir and the Making of Gymnopédie No. 3

When Erik Satie published the Gymnopédie No. 3 in 1888, his musical success and celebrity was just beginning. The year before, in 1887, Satie had been formally discharged from the French military service after a long bout with bronchitis. Upon his release, he moved to Paris’s famous Montmartre district. There, taking up a bohemian lifestyle, Satie frequented a cabaret called Le Chat Noir, where he was soon hired as a pianist. A small, two-room cabaret that was popular with poets, musicians and painters, Le Chat Noir sported an atmosphere and décor that was as unusual and eclectic as the musical style of Satie’s Gymnopédies. And it was indeed during this period of employment at Le Chat Noir, that Satie wrote all three of his Gymnopédies, completing the Gymnopédie No. 3 on April 2, 1888. “The result,” says musicologist Mary E. Davis in her biography of the composer, “is an ethereal and atmospheric music that must have sounded right at home in the oddly appointed rooms of the Chat Noir” (Reaktion, 2007).

although I admire Ciccolinis’ performances in general, I find his Gymnopodie a bit too fast for my taste.. I feel it much more haunting in style.with gentle crecs.and decrecs. and subtle rubato effects.. I have taught this many times and will continue to do so . It’s more difficult than it appears ….Rivoli Iesulauro

Thank you for sharing your approach–interesting that you strive for a more haunting style!

I feel the fist performance superior to Cicc0linis although he is certainly one of todays great pianists Rivoli