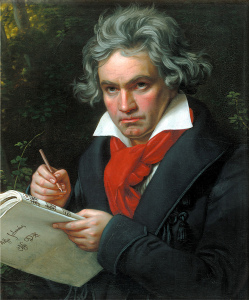

The first movement of Beethoven’s “Moonlight” Sonata is always a source of great delight and fascination. As a Steinway artist and a teacher, I have played and taught this piece—more formerly known as the first movement of Beethoven’s Sonata No. 14 in C-sharp Minor—so many times. It is a pleasure to share my interpretive and technical suggestions here, as part of GRAND PIANO PASSION™’s well-regarded Classical Piano Music Amplified™ series.

Rubato and More in Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata

From all accounts of Beethoven’s playing, he brought audiences to tears by the expressive power of his performances. Yet the Moonlight Sonata is not by any means easy to play from an interpretive viewpoint. The continuous triplets, while wonderful when handled well, can be quite tedious if played mechanically. Rubato, color, and dynamics are essential.

My suggestion regarding rubato is to set a tempo from which you can get both faster and slower so that there is a continuous subtle change of rubato.

Be sure to experiment with the angle of your finger, and the una corda pedal, to change the color and texture of sound. Where Beethoven does not give dynamic indications, feel free to decide what the music is saying to you. Remember you are always telling a story, and that story is up to you. One of the many magnificent aspects of music is that it can and should come to life differently in each performer’s hands.

A Historical Note on Freedom

It is quite significant that Beethoven called this piece “Sonata quasi una fantasia,” as I believe that is an indication of freedom. At first glance, this part of the title, translated as “a sonata in the manner of a fantasy,” seems contradictory. Is the work a Sonata or a Fantasia? I believe this indication by Beethoven clearly represents a movement from the traditional classical sonata. Beethoven is calling for a freedom of interpretation that a Fantasia would imply, as many started as improvisations.

Some Key Measures in the Moonlight Sonata First Movement

What follows are some interpretive suggestions for specific measures in the first movement of the Moonlight Sonata:

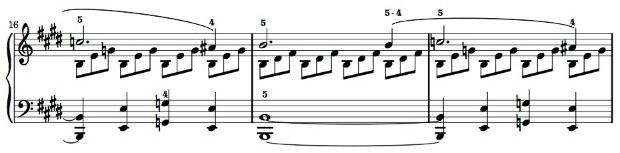

- Look for spots where the left hand has significance, such as measures 16–19.

- Don’t neglect the dissonances in measures 16 and 18 and then again in measures 51 and 53.

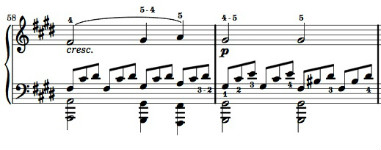

- The alternating melody from the treble to bass in measures 28–30 should be clearly brought out.

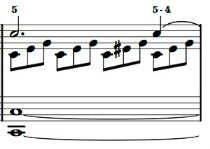

- I think the beautiful effect from measures 32–40 clearly call for an improvisational character.

- Think about how you want to project the wonderful moment at measures 56–59 which I find triumphant.

Bringing Out the Top Voice in the First Movement of Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata

The Moonlight Sonata’s first movement in general takes great control. I would advise an approach of a very close finger to the keyboard, so that you have the greatest control of the sound you produce.

I would start the piece with the damper pedal down, as you will have more control over the volume. That way you do not have to strike the key with enough force to lift the damper and you can whisper.

Bringing out the top voice from measure 9 and in all other places is not easy, as we are required to do it with the weaker fingers while the stronger ones play the accompaniment. Practice this by exaggerating the effect. Play the top voice forte and the accompaniment pianissimo. That will give you the control to create any balance you desire between the voices, as well as the flexibility to vary the balance between the two as you move throughout the piece.

Three Different Renditions by Concert Pianists

Claudio Arrau: Arrau remains one of my favorite pianists. Listen to how he sets the tempo and then uses the rubato to move away from it and then back to the tempo. It is a constant fluctuation that breathes new life into the music every time he makes a change. And listen to the depth of emotion.

Rudolf Serkin: His performance of the Moonlight Sonata is more structured. Notice how the triplets are more even. But also note that this is not simply a mechanical reading, but his rubato occurs in larger areas. It is very subtle, but wonderful nonetheless.

Elly Ney: You may not be familiar with her name. Elly Ney was a student of Leschetizky, who was a student of Beethoven’s student Czerny. So the lineage is very close to the composer. This recording was made in 1964, just four years before her death. Listen to the wonderful rubato and great emotional scope of her playing. I am afraid that many critics would say that she distorts the music, but I think it is just perfect, and she has the connection to Beethoven to justify it. If only more pianists played this way!

Historical Context for Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata

This great work written in 1801 marks a further progression in Beethoven’s movement toward Romanticism. The work gained great popularity during Beethoven’s time, to the point that Beethoven complained to his student and confidant Karl Czerny, “Surely I’ve written better things.” The term “Moonlight” was not given to it by Beethoven, but after the composer’s death in 1832 by the poet and writer Ludwig Rellstab, as the music reminded him of moonlight over Lake Lucerne.

Those ascending and descending diminished chords in the first movement. Does anybody play them as triplets as is done in the rest of the movement, or does everybody play them as duplets at the same tempo. It seems to me playing them as true triplets, although more difficult, would flow better and keep with them character and mood of the rest of the movement.

Jon, here is Cosmo’s response:

Dear Jon,

Thanks so much for your thoughtful and insightful comment and question. One of the many things I love about music is that while certain things are right or wrong such as notes or rhythms, many things are up to us as interpreters and as such are filtered through our own personality and musical sensibility, and our ideas may change over time as we live with and think about a piece of music. I think this is one of those passages. The work is monumental, but we all have to deal with the issue of the constant triplets and how not to make them sound at all tedious. I can tell you what I prefer, but ultimately it is up to you. I like the duplets, because for me it adds tension at that moment and breaks the continuous feel of triplets and then when we return to the triplet feel, I think there is a freshness about it. However that said, you make a good point that the triplets can be maintained in this passage, but if you do this, I would suggest a judicious amount of rubato, dynamics, and color change to offset that continuity. I know I am not giving you a definitive answer, but I do believe it is an interpretive one, and applaud your diligence, thoughtfulness, and intelligence in how you approach your study.