The Rachmaninoff Prelude in G-sharp minor, published in 1911, with its tenor melody and rippling soprano accompaniment, is a satisfying challenge for amateur pianists and adult piano students alike. I explore a number of technical and interpretative aspects of the piece, as part of Grand Piano Passion™‘s well-regarded Classical Piano Music Amplified™ series.

“I’ve always found this piece to have a wide emotional range – it’s a combination of delicate and ethereal versus thunderous and nervous energy,” says Christina Kim, an amateur concert pianist in an email interview with Grand Piano Passion™.

Christina Kim in concert

Kim has performed the Rachmaninoff Prelude in G-sharp minor twice and will do so again in November with the New York Piano Society (NYPS). The NYPS is a nonprofit for talented performers whose profession lies outside of music performance. By day, Kim designs for her brand, ZuZu Kim.

Natasha Paremski, classical concert pianist and NYPS artistic director who joined Grand Piano Passion™ for an audio interview, believes that playing the Rachmaninoff repertoire, including the Prelude in G-sharp minor, creates a sense of catharsis. “The music takes you for a ride,” she says. Paremski and the NYPS will hold a Rachmaninov Sesquicentennial Celebration concert on Sunday, November 5 at 1pm, at the Kaufmann Concert Hall at the 92nd Street Y. (Tickets are $35 general admission, $10 students and seniors, children 17 years old and under free.)

On the eve of the concert, Kim and Paremski offered their perspective on how to learn and absorb the Rachmaninoff Prelude in G-sharp minor.

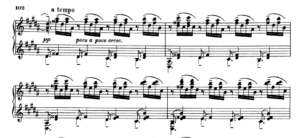

Tenor Melody in the Left Hand

One technical challenge is that the left hand carries the melody with long, singing lines and requires clear voicing. To address this, Kim reports that she tries “to accentuate the left hand’s melodies while playing the right hand more softly and with more legato than we normally hear.”

Right Hand Technique in the Rachmaninoff Prelude in G-sharp minor

The shimmering texture of the right hand throughout the piece is another technical challenge. “I play it with a very light and even touch,” Kim explains. “I practice the right hand part slowly, making sure that each note is articulated, then resting my fingers on top of the keys while releasing all tension before playing the next note. I allow my arm to feel weightless, the wrist very free, with absolutely no tension. I make sure that I play each note clearly, close to the keys. Allowing my right hand to hang loosely, hanging down a little from the wrist, seems to make it more supple.”

Developmental Section in Measures 24 to 30

In measures 24-30, as the music ascends to a climax, the right hand takes on thirds and chords, creating what Kim describes as a series of “intensifying ripples.”  She notes that when playing the right hand, “I make a very free, very light, and quick rotation of the wrist while slightly emphasizing the top note. I release the thumb immediately throughout these measures. I regard the thumb as an extra finger that has absolutely no muscular tension and feels as if it’s just hanging.”

She notes that when playing the right hand, “I make a very free, very light, and quick rotation of the wrist while slightly emphasizing the top note. I release the thumb immediately throughout these measures. I regard the thumb as an extra finger that has absolutely no muscular tension and feels as if it’s just hanging.”

Anchoring Tempo Changes

In the short three minutes required to play the prelude, the music has a number of tempo changes, unusual for Rachmaninoff, points out Paremski. For example, Rachmaninoff marks measure three (M3) as ritardando, M4 as meno mosso (literally less motion, meaning a slower tempo), M5 as accelerando, and M6 as a tempo, e.g. a return to the original tempo.

Paremski counsels that pianists should be very conscious of the a tempo markings. “So you have to remember your first tempo, your primo tempo, and then every time you come back to the a tempo,” that you play the tempo exactly the same. “Those [a tempo moments] are your pillars when you’re telling your story to your audience,” she concludes.

Tempo Rubato in the Rachmaninoff Prelude in G-sharp minor

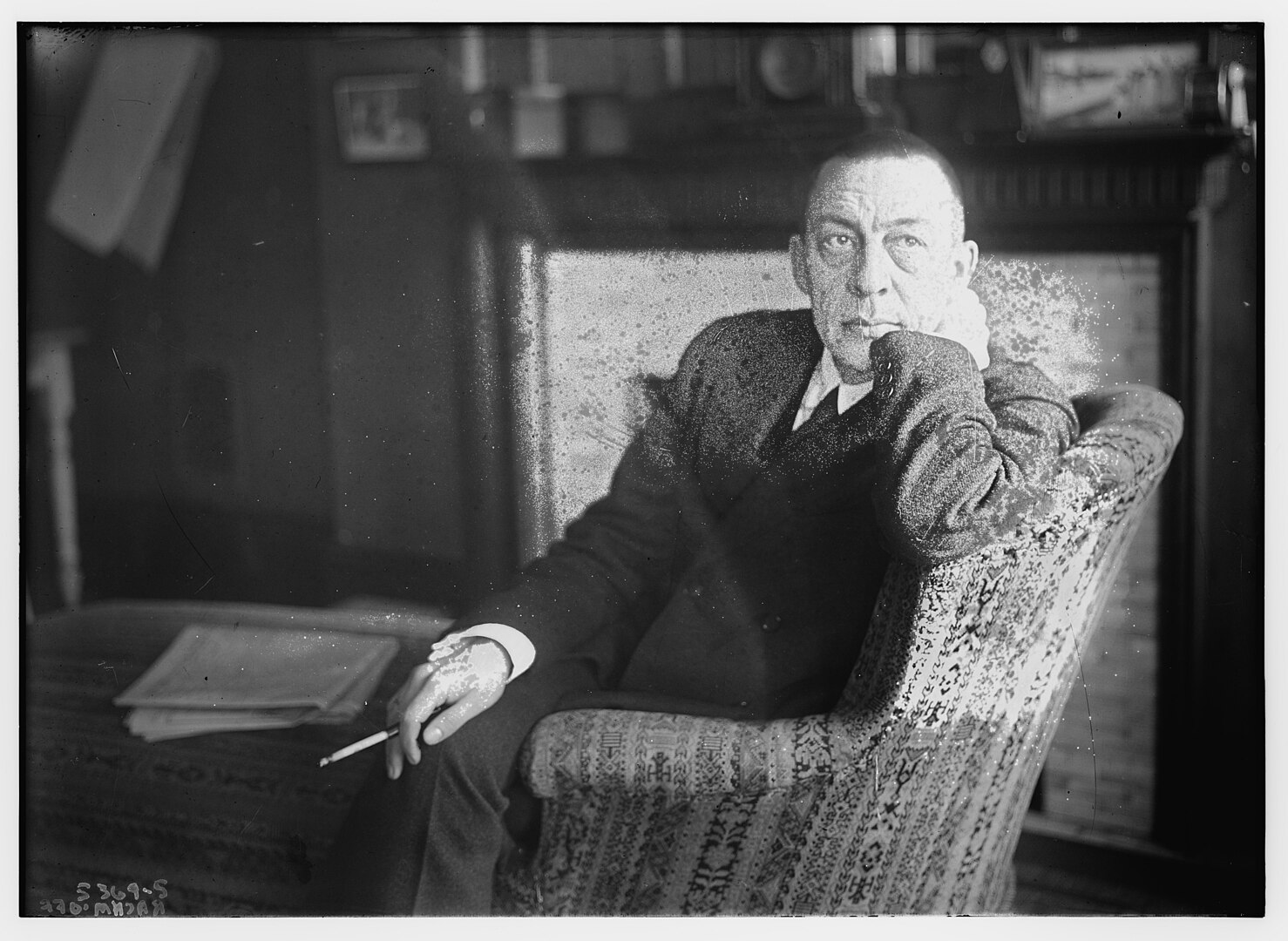

Related to the frequent tempo markings is tempo rubato, a technique in which pianists vary the tempo, pushing the speed of some phrases or sections, lingering over others, to give the music its emotional depth. “My general comment about Rachmaninoff is that unless he tells you to take time, don’t take it. Don’t gild the lily!” Paremski declares. “Do not make the music saccharine.”

Describing her own approach to Rachmaninoff as stoic, Paremski muses Rachmaninoff came from a noble family and was reserved as a person.

The Rachmaninoff Sesquicentennial

Asked to describe what makes Rachmaninoff’s music timeless, Paremski declares “Catharsis! I think there’s a lot of emotional catharsis in Russian music in general, and especially in Rachmaninoff.”  The composer’s original and rich melodies, dense harmonic fabric, and polyphony all contribute to the sense of emotional release. “All of that translates to the audience being captivated,” Paremski says.

The composer’s original and rich melodies, dense harmonic fabric, and polyphony all contribute to the sense of emotional release. “All of that translates to the audience being captivated,” Paremski says.

Rachmaninoff’s popularity with audiences was one reason why Paremski has chosen to hold a sesquicentennial celebration, honoring the 150-year anniversary of the composer’s birth. For the performing members of the NYPS, his music offers “a very cathartic escape from their day to day lives, from whatever their day jobs may be.”

Kim adds that the NYPS has “inspired and pushed me to challenge myself and consistently practice and keep the music and playing alive in my life.”

Two Favorite Renditions by Concert Pianists

Kim finds Rachmaninov’s interpretation of his own work to be melancholy and intimate. “Overall, the piece sounds softer than commonly played,” she says. “He plays with an understated virtuosity and highly convincing expression of the soundscape he intended for this prelude. His long-line melodies are haunting.”

Christina also recommends Vladimir Horowitz’s interpretation of the Prelude in G-sharp minor, which she finds ” impassioned and poetic. His unparalleled dynamics are incredibly effective, and the phrasing is highly emotional,” she enthuses.

A Note On the Spelling of Rachmaninoff. The New York Piano Society uses a newer spelling of the composer’s last name, closer to the Cyrillic pronunciation, of “Rachmaninov.” Popular usage may very well gravitate in that direction. In the meantime, we are using the more traditional spelling of “Rachmaninoff,” in keeping with Google Search and Wikipedia.

0 Comments