Almost everyone has struggled with at least one subject in high school. Mine was language. For three years I endured the steely gaze of my French teacher, a lean, sour-faced woman named Ms. Kopp. My futile struggle to conjugate verbs was trumped by her failure to smile. It’s ironic then, that 40 years later, not only do I have a working knowledge of French, but I have willingly immersed myself in a new language: music.

Why is it, I ask myself, when I’m already juggling piano lessons, practice time, writing, and caring for a family, that I have decided to study music theory? I’m not a conservatory student and am well past the age when a career in music is a viable option. I’m an amateur pianist. Isn’t that enough? But the fact is, that after these two years of theory, I can’t imagine a better way to deepen my piano study.

Several years into adult piano lessons, my teacher, Denise Kahn, in showing me patterns within the music, spoke of intervals. Hmmm, intervals? Had I been faking my musical knowledge well enough so that she assumed I knew what she was talking about? Perhaps in reaction to my silence and blank stare, she briefly explained the meaning of a second, a third, a fourth, and a fifth. It was clear to me that she was talking about the distance between two notes and I devised a way to determine an interval by counting the lines and spaces between the notes. If the notes were stacked on top of each other, it was a second; one line between the two, it was a third; a line and a space, it was a fourth. I had no idea what it all meant, but I was able to do the calculation.

As I progressed in my piano study, however, it became obvious that intervals were just the beginning. I didn’t know what information I was missing, but I knew I was missing a big chunk. Denise suggested I contact Stanley Dorn, a theory professor at both Mannes School of Music and Yeshiva University in Manhattan.

Along with two other students of Denise’s, I formed a private class, and we have been meeting every Wednesday for the past two years. For 90 minutes each week, the three of us huddle together as Stanley takes us through the lesson.

“Music is a language,” Stanley told us during one of our first classes. Really? A language? Hadn’t I left all that behind in high school? Spying our mystified faces, he grinned and continued, “And, like any language, music has its own vocabulary, grammar, and punctuation. Notes are not merely dots on a page; they have a relationship with each other throughout a composition. Learning theory will help to unravel how that relationship works.”

Scribbling his words into our notebooks, we glanced at each other anxiously.

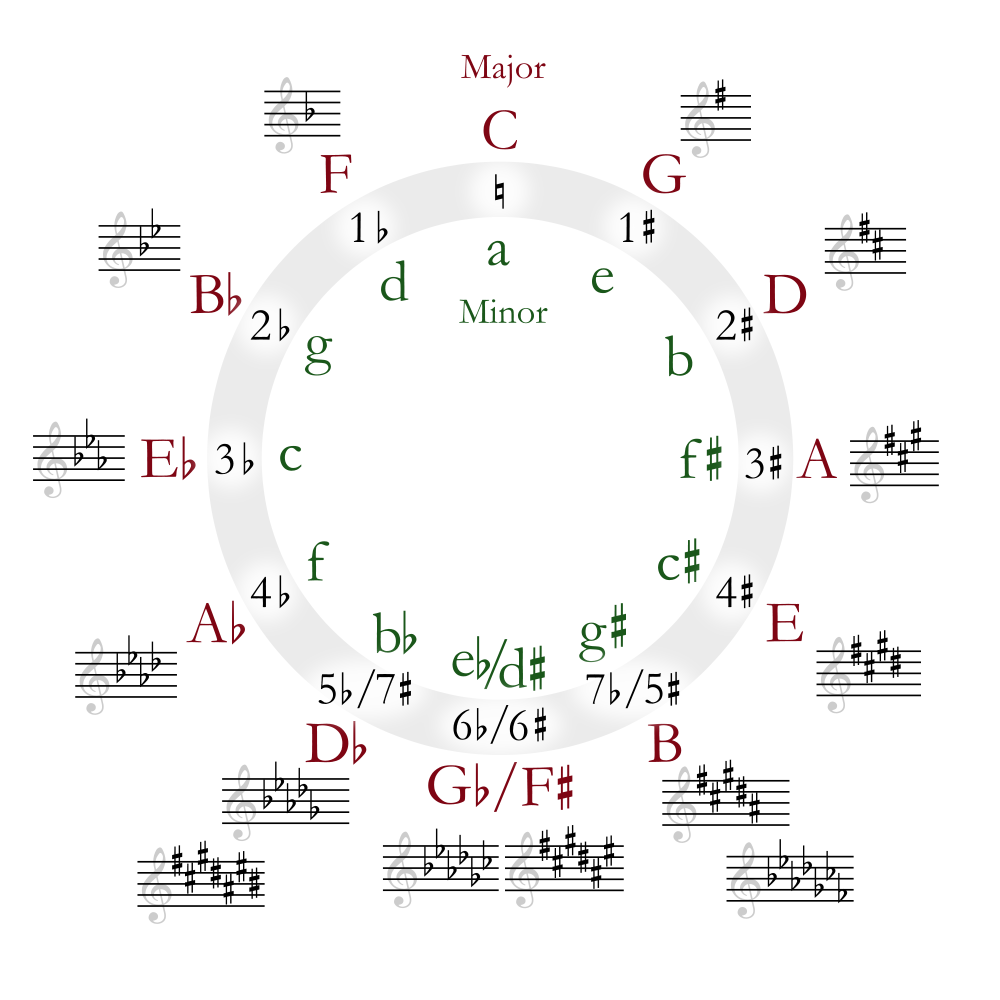

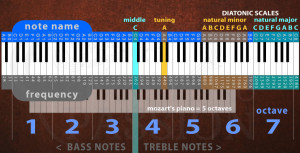

Our classroom tools include a dry erase board lined with staves; red, blue, and green markers; and, of course, a piano. We started our course using the same workbook as his college students, and each week Stanley marked our mistakes in the homework assignments with red ink. Topics have included the circle of fifths, whole steps, half steps, scales, triads, and the ever-confusing seventh chords. Yet as we learned how triads and seventh chords are formed, I slowly began to understand what Denise had been trying to teach me those many months ago about intervals.

Lately, we have been focusing on the harmonic structure of music, studying simple chord progressions. “Music theory helps a performer to understand this structure—the story the composer is telling in the music and the emotional content inherent in it,” Stanley said. “This understanding will help a pianist in determining how to perform the music. For instance, if the last few chords of a phrase contains a V chord, the dominant of the key of the composition, and then resolves to a I chord, the tonic, you will know by the rhythmic position of the two chords, which should be relatively more accented. And if a phrase contains a dissonant seventh chord with accidentals foreign to the key, it is signaling a possible change in the direction of the music and it should not be overlooked.”

Wow!

Before I began studying theory, my instinct was to try and hide a dissonant seventh chord by playing it pianissimo. With the insight I have now, not only can I recognize a seventh chord in the music; I know that this seventh chord may be foreshadowing a transition in the music. Recently, I was able to analyze the Mozart Rondo in D Major I was learning. Towards the end of the piece there is a measure-long trill, which I realized was just an extended V chord. With this recognition, I understood that the following note, D (the tonic), would then resolve softly. In that same Rondo, I was able to identify a dominant seventh chord occurring at the end of a passage where Mozart had already modulated to the dominant key of A. That dominant seventh in the key of A signaled a change in the music—bringing us back to tonic, D major.

This discovery is thrilling, like a child taking her first few steps. Music theory is providing me with invaluable tools, a road map for each new musical journey. By combining music theory with regular piano lessons, I am well on my way to deepening my understanding and passion for this particular language: music.

Great article!

Thank you Tamara!

My daughter, having studied classical music at Bucknell University for two and a half years and now voice at Berklee College of Music in Boston (for another 3 and a half years) has had six semesters of music theory and still struggles with it She explains it to me this way: “It’s like learning Greek, in Braille.”

Neither math nor language were my strong points in school, so I will take her word for it.I applaud your efforts, Robin. Nicely written too!

She’s right! But for some strange reason, it makes sense to me, and more importantly is helping me become a better pianist. The extra plus is that it gives me something to write about! Thanks for kind words, Ryder.

Robin,

I just saw this. I applaud you for taking this ambitious step. I glaze over when my flute teacher talks theory; I’m just happy to play the right notes. Maybe this will change??

Great article.