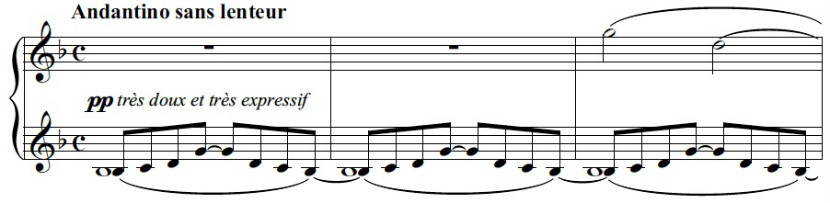

In the Debussy Rêverie, the best way to communicate the music’s natural rises and falls is through your own physical breath control. In this article, part of GRAND PIANO PASSION™’s well-regarded Classical Piano Music Amplified™ series, I look at the Debussy Rêverie from multiple perspectives, including how to pedal to create resonance, the argument for flexibility in interpreting the tempo, and two rubato-infused performances from concert pianists.

Breath Control in the Debussy Rêverie

For me, the most important aspect of technique in Rêverie has been the breath: just as an opera singer might naturally breathe where phrases begin and end, there is a mental and physical pause, clearing, or “reset” with each phrase. I have found that the best way to communicate natural-sounding rises and falls in the music is to emulate it and internalize it by way of my own breath control, as opposed to orchestrated phrasing purely through finger mechanics. The audience then tends to synchronize with the pianist and may even find themselves breathing to the phrasing carried out by the pianist.

At the start of the Debussy Rêverie, with the very first motif—those four simple notes—I feel I can communicate the mood and tone of the entire piece. Right before the piece, I breathe in, and then that first phrase of the Rêverie is like the exhale. It’s a slow release of breath, setting the pace for a calm and peaceful experience for the audience.

Pedaling in the Debussy Rêverie

When playing Debussy, it’s seldom that I’ll actually put the pedal all the way down, and at the beginning of Rêverie, I keep it only about a quarter or a third of the way depressed. I don’t use the pedal to sustain, but to create resonance and atmosphere. Rather than the crisp, clear type of concept I find in Baroque music, I’m really after a continuity of thought—a fluidity, like when you throw a pebble into a pond, and the ripples move outward.

To blend and overlap chords, I partially lift up on the sustaining pedal and allow some of the residue from the previous tones to blend into the next as I bear down slowly into the pedal again. In other words, I gauge when and where I want to completely clear the sound by lifting up completely on the pedal and where I want to have the tones wash into the next.

I live in Florida in the countryside on a lake, and it is green and verdant year-round. The air is fresh, with birds chirping by day and crickets by night. I endeavor to embody and project the peace and tranquility of my environment in my performance of the Debussy Rêverie.

Performance Norms from Debussy’s Era

The performance boundaries in Debussy’s day were freer and less formal than what we are accustomed to today. Some musicologists point to more mistakes and wrong notes in performances of legendary concert pianists of the early-to-mid-20th century as compared with the dominance of sanitized perfection in modern-day concert performances. Other musicologists cite that even the markings we see in modern editions of music do not mean what they used to mean. Roberto Poli argues in The Secret Life of Musical Notation: Defying Interpretive Traditions that the crescendo/diminuendo markings of the 19th century were actually rubato indicators in the music of Chopin and his contemporaries.

Differences in performance norms, then and now, present a chasm between the way the Debussy Rêverie is interpreted today versus in his own day. In the words of Nicholas Cook and Mark Everist in Rethinking Music, “It seemed natural to Debussy that different performances would involve different tempo fluctuations: one naturally added them to a performance. On this account, hearing Debussy play the piano is not unlike hearing a poet read his work: the poet is not reading the poem with an accent because we must always hear the poem in that accent, but simply because that is how he speaks. From other performances we can confirm that this is simply the way Debussy plays. . . . For an editor of the period, it was natural for a performance to have tempo variations which were not written in the score; even in 1910 it was clearly recognized that a score is not a complete set of instructions, and a performer is not simply an executant.”

Tempo, phrasing, dynamics, and accents are more of a guideline and a framework, with the ultimate performance authority being the pianist. The composer and pianist in partnership, each takes a virtually equal role in the crafting of the sound and story, with the performer telling it as only he or she can.

Aldo Ciccolini and Kathryn Stott Play the Debussy Rêverie

Along with my rendition above, Aldo Ciccolini’s and Kathryn Stott’s recordings of the Debussy Rêverie provide additional ideas for interpreting the piece. Both of these versions prefer a slower tempo and incorporate a lot of rubato, but the mood and the way each performer has internalized the composition is completely different.

In Ciccolini’s recording (left), the mood is romantic, dreamy; there’s a sense of abandon, and there’s a joy to it. Stott’s interpretation (right), on the other hand, sounds more melancholy—which might be more authentic to what Debussy intended, as he has said that when he wrote Rêverie, it was one of the saddest times of his life.

One way to create a more melancholy sound, as opposed to a more joyful sound, is through touch: you can bear in more, make the phrases heavier. Stott did so, creating an atmosphere of nostalgia. Stott also ends phrases in a languishing sort of way, finishing them more slowly, like the way you speak the end of a sentence when you’re sad; whereas in Ciccolini’s rendition, he ends each phrase and it flows right into the pickup of the next phrase, without the same finality.

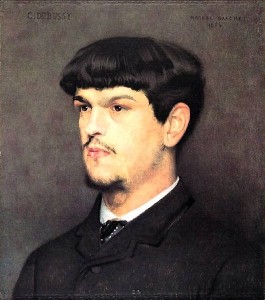

An Early Debussy Work

Claude Debussy composed Rêverie in 1890, and didn’t regard it as a major work, but more of an experiment during a period of financial difficulty. Pursued by creditors at the time, Debussy complained in a letter to a friend that “the various lessons I rely on for my daily bread have gone off to the seaside, without a thought for my domestic economy, and the whole thing is a good deal more melancholy than all the Ballades of Chopin” (from The Life of Debussy by Roger Nichols, Cambridge University Press, 1998).

Rêverie was one of Debussy’s earlier works, characterized by their abstract titles, as opposed to the descriptive titles and clear storytelling of his later works. Writes Victor Lederer in Debussy: The Quiet Revolutionary (Amadeus Press, 2007): “While his later piano works are, without exception, greater, these early pieces point clearly toward those he composed after 1903.” The early pieces, including Rêverie, were “composed before or as Debussy developed his pictorial style.”

Debussy’s Reverie is one of my favorite pieces! I will have to dust it off and take your advice re: breathing and pedaling. And the historic context is very informative. Thank you!

So glad that you found the advice on technique and the historic context helpful. It’s one of my favorite pieces too. I first learned it when I was 13!