The repeated tenor notes, which patter underneath all but a few of the measures in the Chopin Raindrop Prelude—first A-flat, then G-sharp, then back to A-flat again, so evocative of raindrops—make the piece almost wholly unique in classical piano music. In this article, part of GRAND PIANO PASSION™’s well-regarded Classical Piano Music Amplified™ series, I look at the Chopin Raindrop Prelude from multiple perspectives, including the technique to accomplish the repeated tenor notes, vivid performances from concert pianists, and how the music fits into Chopin’s larger body of work.

The Repeated A-flats and Tempo Rubato

The repeated A-flats in the Chopin Raindrop Prelude ought to be “organic, natural, with a mesmerizing quality,” says Mark Pakman, Adjunct Professor at the John J. Cali School of Music. The corollary is that those tenor eighth notes repeating throughout the music—A flat, then transformed to G sharp, and then back to A flat again—should be played more or less strictly in time. Exceptions would be at the end of a phrase, such as the group of seven treble notes closing out measure four. This means that tempo rubato in the Chopin Raindrop Prelude should be subtle, never exaggerated or maudlin.

Chopin’s own correspondence supports Professor Pakman’s view. “Imagine a moving tree with its branches swayed by the wind. The trunk moves in steady time, the leaves move in inflections,” Chopin wrote to Franz Liszt, his friend and fellow composer. In other words, rubato is discreet, like the gentle rustling of tree leaves. “Do you see those trees?” Liszt later wrote, perhaps a vein of sarcasm in his tone. “The wind plays in the trees, life unfolds and develops beneath them, but the tree remains the same—that is Chopin’s rubato.” (This correspondence described in Chopin by George R. Marek and Maria Gordon-Smith, Harper and Row, 1978.)

The Raindrop Prelude’s Storm Section

The second section of the Chopin Raindrop Prelude marks several notable shifts in the music. The key changes from D-flat major to C-sharp minor, and the melody moves from the treble into the deep bass. The mood of the music changes as well, from ruminative, rapt musings, perhaps the happy thoughts of Chopin newly enamored with Sand, to a to a brooding feeling that explodes with octaves in the bass. When I play this music, I imagine that the chords shifting in the bass are storm clouds gathering force, until thunder rips through the sky in the form of fortissimo E and B octaves.

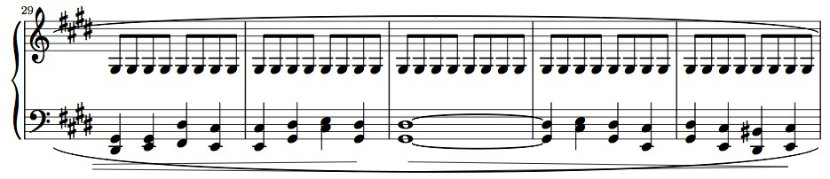

In terms of technique required to play this section, I recommend using the soft pedal in measures 28 through 34, and again in measures 44 through 50, the point in the music where the rainstorm brews. In these measures, be sure to pedal after every chord change. With the notes this deep in the bass, the overtones are closer together, and a lack of pedaling can create an unintended, muddy effect. Imagine that the the two-note chords in these measures are a pair of bassoons, counsels Mark Pakman, and let both notes sound equally.

A G-sharp very low in the bass in measure 39 (and again later in measure 55) precedes the thunderous octaves. Let the rich sound of that note underpin the rest of the measure, by clearing and then depressing the pedal just before playing the G-sharp. Although it looks like a grace note, the G-sharp should be played with a decided emphasis, with plenty of arm weight. Similarly, in the E and B octaves in the ensuing measures, play them with arm weight so they boom out like deep thunder, without sounding harsh.

Two Legendary Interpretations of the Chopin Raindrop Prelude

Martha Argerich and Vladimir Horowitz serve up the Raindrop Prelude with entirely different tastes, the contrast instructive for adult piano students.

Martha Argerich plays the Chopin Raindrop Prelude with a relatively fast tempo. Her tone shimmers, pure liquid in the first section, but what is most noticeable in her masterpiece of the music is the tempo rubato. In the very first phrase, her use of rubato takes your breath away. Rather than a few tree leaves rustling, the tree trunk leans to one side, then bends to the other, yet in a way that somehow feels natural, in keeping with the music.

In contrast, Vladimir Horowitz delivers the Chopin Raindrop Prelude at a slower pace and with far less tempo rubato, achieving Mark Pakman’s ideal of a mesmerizing performance. In the middle storm section, Horowitz thunders the fortissimo E and B chords with a magnificent bass sound. My favorite moment is the sweet ringing sound to the melodic notes in the chords that follow the storm.

The Love Story Surrounding the Chopin Raindrop Prelude

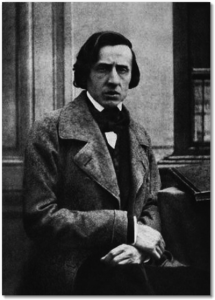

In the fall of 1838, Frédéric Chopin set off from Paris for what his friends considered an ill-conceived expedition: to spend the winter on the island of Mallorca just off the coast of Spain with his lover of five months, George Sand. The letters Sand and Chopin sent home to Parisian friends described trials: the difficulty in securing lodging, the hostility of the locals. They eventually settled in a deserted stone monastery on a high plateau overlooking the city of Palma, a location vulnerable to rains from nearby mountains.

Late one evening, George returned from a walk to find Chopin at the piano, immobilized by fear. In Histoire de Ma Vie, Sand wrote that Chopin “had a vision of himself drowned in a lake. ‘Heavy, icy, drops of water,’ he said, ‘were falling rhythmically upon his heart,’ and when I made him listen to the raindrops which were, in fact, dripping with regularity upon the roof, he denied that they were what he had heard.” Whether Chopin composed the Raindrop Prelude during his Mallorca trials or whether in fact he had begun the piece earlier in Paris—Chopin scholars do not know—the piece has become associated in the minds of classical piano music fans with the incessant rain that pelted Mallorca that winter. (This excerpt is from Nancy M. Williams’s memoir-in-progress, Forgotten Prelude.)

The Chopin Raindrop Prelude as Part of a Set

The Raindrop Prelude is part of a book of 24 preludes, 12 in each major key, 12 in each minor, the Raindrop Prelude written in D-flat major. Chopin sold the preludes to Camille Pleyel, the Parisian piano manufacturer and music publisher. In exchange, Pleyel agreed to ship a piano down to Mallorca, the destined location for Chopin’s tryst with the French novelist, George Sand.

During Chopin’s lifetime, his peers lauded the preludes. “These are not, as the title would have us think, pieces intended to be played as introduction to other music,” explained the composer Franz Liszt. “These are poetic preludes… everything is full of spontaneity, elan, bounce.” Composer Robert Schumann wrote that in each prelude, we find Chopin’s “refined, pearl-studded writing… we recognize him even in the pauses and in his ardent breathing.”

look inside  |

Chopin – Preludes By Frederic Chopin (1810-1849) and Fr. Edited by Brian Ganz. For Piano (Piano Solo). Schirmer Performance Editions. SMP Level 10 (Advanced). Softcover with CD. 96 pages. Published by G. Schirmer (HL.296523)  (2) …more info |

look inside |

The Complete Chopin Preludes (Op. 28, Op. 45) (A New critical Edition). By Frederic Chopin (1810-1849). Edited by Jean-jacques Eigeldinger. For piano. This edition: Urtext. Urtext. Romantic Period. Difficulty: difficult. Collection. Introductory text, performance notes and critical commentary. 68 pages. Published by Edition Peters (PE.P07532)…more info |

I am very puzzled by what you are playing in measures 18 and 19. I am no expert, but it does not seem to reflect the written music and I double checked several times. Also listened several times to that part in the examples on the page by Argerich and Horowitz and they seem to confirm my impression.

Thank you for writing! There is a glitch at measures 18-19 (1:13-1:19 in the video) where I play one wrong note, then I’m skipping over the next several notes as written and playing a couple of repeated chords instead–the best I could do to transition. This was a live performance. Here’s another live recording of my playing this piece, which does not have the same error: https://grandpianopassion.com/2013/08/19/nancy-m-williams-plays-chopin-raindrop-prelude/

Since my playing does not warrant performance for an audience… I have often wondered about what happens if a mistake is made (or one’s nose itches or some such). So, nice save. I didn’t realize that it was a live performance, and was wondering if you had some other version or something. I probably would not have noticed if this was not a piece I was working on.

Anyway, hope you don’t mind my asking, but was very curious.

I don’t mind your asking at all. My former piano teacher told me that Vladimir Horowitz once bounced a series of erroneous chords down the piano, then got a standing ovation anyway! Not sure if that actually happened, but it’s a good story. :-) Good luck with your practice. The Raindrop Prelude is one of my favorites.