F

or my performance at Carnegie Hall, I wanted to infuse my music with the same emotion I experienced at home. Of course, I was preoccupied with The Dress—what would I wear for such a momentous occasion?—and I was determined not to scar my performance with mistakes. Yet what most mattered to me was the ability to tamp down my nervousness so I could share with the audience the intense feelings the music aroused within me.

The opportunity to perform at Carnegie Hall had come packaged with a master class in performance I enrolled in during September of 2011 with Cosmo Buono, a pianist, and Barry Alexander, an opera singer. The other seminar participants were a mix of amateur adults, like me, and gifted teenagers, some who had placed in national competitions. Once a month we crowded into a practice room on Seventh Avenue to discuss performance strategies and play our music. A few blocks away awaited the majestic Carnegie Hall, where our group would perform in recital in February.

“You will be nervous and you will make mistakes,” Cosmo Buono told the class. “The question is, how will you handle your performance anxiety? How do you plan to recover from wrong notes?” While he spoke, bloopers from previous recitals paraded in my mind: skipping over big chunks of music, leaving off in the middle of a measure, and almost getting caught in an infinite loop while attempting to redo a botched passage. Now it seemed to me that by obsessing over errors, I had frayed the music’s emotional line.

Not long after the master class’s inaugural meeting, the annual holidays sprinted up and ran alongside me. I felt a sweet happiness when I decorated the front of the house with my son Cal and my daughter Mena—with Cal in middle school and Mena in fourth grade, they had opinions on where the lights should go—but the holidays also marked my strained relationships with my parents and sisters.

On a fireplace hook, I hung up the red felt stocking Mom had sewn during my childhood, and placed on the tree’s top branch an angel made from thick yarns glued onto cardboard—my three sisters, scattered around the globe, each had one too. The absence of my childhood family in my life gnawed at me. My parents and sisters each lived thousands of miles away, yet even worse was that I was barely in communication with any of them. I could not bring myself to speak with them—causing one sister to retort that she did not want to hear from me either—because our conversations surfaced painful memories of the past. I needed some time alone to grow up, to develop a sense of myself independent from my childhood family. The piano, I hoped, would help guide me.

By early January, however, I felt only exhaustion mixed in with a ballooning nervousness about my impending recital. On a Wednesday evening, when deep purple clouds made the night seem especially dark, I parked in front of my church, which was holding its weekly Labyrinth walk. Candles flickered in the windows. The Labyrinth, a meditative pathway that wound inwards towards a center, was something I had intended to try for a long time.

* * * *

T

he interior of the church was chilly and dark, lit only by candles. I huddled in a pew, listening to the recorded chant music, while in front of the church, between pews and altar, two dark forms walked the Labyrinth in their stocking feet. Whenever I had gazed at the Labyrinth during the service, the pathway the color of dark chocolate, the edging a light blond, I had figured the walk would take the shape of a nautilus, the path winding inwards, coiling more and more tightly.

The fact that I sat in this pew was somewhat miraculous. My husband, David, and I had joined this church because we wanted Cal and Mena to have a chance at faith. In my childhood home, God had felt hypocritical. Dad insisted that we attend church every Sunday, yet he raged at the disturbance of my piano music. In the summer of my 16th birthday, when my parents divorced, I was forced to quit the piano. A decade later, Mom became religious, attending Mass every Sunday; yet whenever I brought up my childhood, she acted angry and hysterical. She never asked about the piano.

In spite of my past, here in this church, I had found a kind of half-faith, the only faith of which I was capable. When the entire congregation prayed, I could feel intentions radiating from the bowed heads. After a while, I prayed too—at first gingerly, then, as time went on, with more confidence. I prayed for help: to parent my children with love and wisdom, to enjoy a peaceful marriage with David, to give more to others who had less than I, and to be true to my life’s interests, especially the piano.

Now in preparation to walk the Labyrinth, I unzipped my boots. As soon as I began to tread the path, I saw that my assumption had been wrong. The head of the path did not open into the Labyrinth’s outermost ring, but instead sprung directly into an inner branch, which looped up towards the altar and then turned onto the Labyrinth’s outer circle. While I trod the path, I concentrated on keeping my stocking feet from slipping onto the border.

While I wound through branches on the opposite side, I wondered how I would feel when I reached the center. I turned a sharp corner and stepped directly into the Labyrinth’s oval center. When I looked up, I directly faced the illumined cross, two thick perpendicular swaths of wood, hanging over the altar.

In the silvery light, the cross throbbed, and I drew in my breath. Now I will have the thought that will help me achieve a sense of calm, I told myself. Instead, I could think of nothing at all. I became aware of the stiffness in my shoulders, from hunching them towards my neck while I fretted during my piano practice. I gingerly rotated my shoulders, and muscles throughout my body unclenched. My body grew light. When my arms floated out to the side, I could only stare at the cross in wonder.

* * * *

“You must rehearse at home,” said Cosmo Buono, one of the master class instructors, as the Carnegie Hall recital drew nearer. “You must practice walking to the piano and bowing.”

“You must know exactly what you will think the moment before you play,” added Barry Alexander. “You must concentrate, to get into the music.”

At home, I strode into my study-cum-piano room, placed my hand on top of my beloved grand, bowed in the direction of my computer desk with a self-conscious smile, and sat on the bench, pretending to smooth my gown. The Dress was the only element of my planned recital of which I felt confident. I would wear a long sheath of crinkled silk, which a retired designer, now 78 years old, had left over in her Queens warehouse.

Depending on the angle, the fabric sometimes looked lavender, other times sapphire. “When you move at the piano, this will glimmer under the stage lights,” the designer confided to me in her staccato Hungarian accent. She could not remember where she had placed her straight pins, her tape measure, even the dress itself, but she knew exactly how she wanted the gown to fit.

As long as the Queens warehouse did not burn down, as long as the Hungarian designer did not forget to make the adjustments for the final fitting, the gown would be beautiful, but it would not be enough to carry the music. I was to perform Chopin’s Nocturne in E-flat Major and then his “Raindrop Prelude,” on stage for a solid 12 minutes, a long time for an amateur who did not perform regularly.

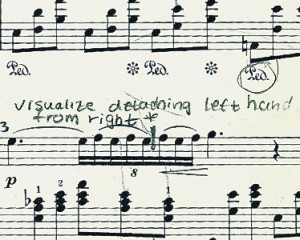

I had memorized my two Chopin pieces in a variety of ways: playing each hand separately, jumping into the music at entry points throughout the score, and even playing some of the measures in backwards order. To allow my motor memory to help carry the music, I would need to zip into a zone of concentration and stay there for the entirety of my performance. Most importantly, I wanted to reach across the barrier of my stage fright, even the stage itself, to offer the fabric of my music woven with emotion. What would I envision the moment before my fingers touched the keys?

I remembered standing in the center of the Labyrinth, my body light and yet filled with wonder. Oftentimes in this very room, when I played the piano alone at home, I felt the same way. Whenever I traveled deep inside my piano music, my mind was at rest, content to allow my hands to shape the chords, while euphoria tingled throughout my body. Perhaps during that moment before I struck the notes, I could visualize the cross.

No, a voice inside of me protested with vehemence. Visualizing the cross would enmesh me in organized religion. Soon I would be writhing in front of the altar (although that didn’t happen at my church) and accosting innocent atheists in the grocery store. Or, perhaps more to the point, I would morph into Mom and Dad, who had piously attended church, yet who both had heaped blame on the other for the chaos and misery in my childhood home.

Perhaps, a small voice suggested, I was confusing my parents with God? I wanted to keep on walking the Labyrinth and praying in church, even if my kind of faith was faltering and hesitant. The Carnegie Hall recital was only a month away. Unless I came up with a better idea, in the moment before I played, I would visualize the Labyrinth cross.

* * * *

A

t Carnegie Hall, the Weill Recital Hall had cream walls, arches bordered by velvet drapes, and gold acanthus branches set high into the walls. The nine-foot Steinway grand sounded pearly yet majestic, the tones catapulting directly into the audience. “You don’t have to worry about projecting your music,” Cosmo Buono advised me during the dress rehearsal from his spot in one of the velvety seats. “The acoustics are excellent.” The hall was unlike any place I had performed before. Even the backstage—where, waiting to perform, I paced back and forth, sequestered myself in a practice room to run through my music, and carefully slipped the lavender and sapphire gown over my head—was spacious and elegant.

Fifteen minutes before my turn to perform, I felt the memory of my parents pressing on me, as though I had to resolve something before I went on stage. I wandered into the stairwell behind the concert hall. I peered down into what seemed an infinite number of handrails and staircases, the view stark and monotonous, perhaps the way life often had felt to my parents. They had acted selfishly, but they also had struggled, Dad with his alcoholism, Mom with her overwhelming feelings of inadequacy.

But they did not belong here in Carnegie Hall. My performance was about keeping a pact with myself, about developing my independence, about creating a central musical line inside that would form the core of my being. I cupped an image of my parents into my hands and released them into the stairwell. They floated downwards.

On the other side of this stairwell, in the concert hall, in the audience, sat my family, David, Cal, and Mena, as well as 20 of my friends, some of whom had traveled by planes, trains, and buses expressly for this event. I wanted to share with them and the entire audience the feelings the Chopin music evoked: ecstasy, anger, gentleness, and even this wisp of forgiveness now wafting after my parents down the stairwell.

The stagehand opened an enormous door cut into the wall, and I strode out onto the stage. In the second row of the audience, I caught sight of my family, David with a reassuring attentiveness on his face, Cal with an earnest encouragement, and Mena, her large eyes filled with amazement. I sat down at the bench and looked across the open plane of the Steinway, the strings converging in their comforting, predictable pattern. Shoulders back and down, I whispered to myself, and I allowed my shoulders to loosen, floating over my torso and hips.

On the wall beyond the piano, I saw the cross, two simple pieces of painted wood, silvery and illuminated as I had seen it that night from the Labyrinth’s center. I nodded in recognition. In a quick motion, my hands swung forward, and I struck the opening notes.

Dear Nancy,

I read your marvelous essay, and listened to your play Chopin, the steady beat of the rain with all that it conveys–nourishing, re-birthing the land, the spirit, the soul. It’s all there, the rumbling sometimes threatening sky mimicking anxiety, the edge of losing control through worry, and then back again, reassuring, the rain, the blessing of rain.

Both essay and performance are stellar.