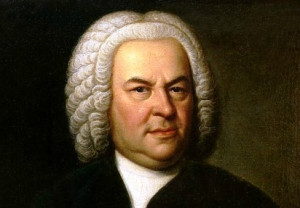

or a train journey down south, Paul Elie took along a triple-CD set of Bach’s St. Matthew Passion. “I was overwhelmed by Bach on that train like Jonah swallowed by the whale. The train pounded down the corridor to Washington, taking on bureaucrats. The Passion sounded out in the foam-tipped headphones. . . . Past Washington, the stops spread out and civilization fell away from the trackbed. . . . Bach was taking us to another country; we were there, and almost there.

“When [the Passion] ended, I put on [a] B.B. King disc, then took it off. The music of Bach was resounding. I rode the rest of the way idly, not reading, not listening, just sitting in the presence of a sound that would not subside.”

After I read this passage in Paul Elie’s Reinventing Bach (Farrar, Strauss, and Giroux, 2012), a masterful book that is readily savored, I realized that the author’s train trip had constituted a supreme act of listening. In Reinventing Bach, Elie’s scintillating descriptions of Bach’s music—The Well-Tempered Clavier is “a many-sided figure of wholeness, harmony, and radiance”; it is “Bach’s periodic table of the elements”—are proof that in preparation for this book, he listened with the same avid contemplation to wide swaths of the recorded Bach repertoire.

*****

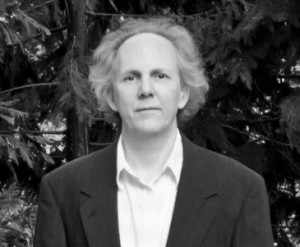

In my own study of classical piano music, the ability to listen eluded me. A few years into my adult piano lessons, I announced to my teacher, Stephen, that I wanted to study some of The Well-Tempered Clavier’s 24 paired preludes and fugues.

He shook his head, his long hair swishing against his collar. “Too hard.” Perhaps at my expression of disbelief, he held up his hand. “The notes are not that difficult, but the fugues have three, four, or even five voices. First you’ll have to learn to hear multiple parts in your head.”

Sometimes during my lessons, Stephen complained that while my fingers went through the motions of playing, I did not listen to my own music. I needed to hear the melody as an integrated song that embraced a feeling or perhaps even encapsulated a story. I could see why he balked at a fugue with three voices if I did not truly register even a single-voiced Chopin prelude. “I could work hard on hearing the voices,” I said.

“Start with the Two-Part Inventions,” Stephen advised. I sagged towards the bench: I did not want to waste time on this considerably easier cycle. My piano teacher was 15 years younger than I, our age gap suggesting I could overrule his recommendation of the Two-Part Inventions.

*****

For Bach, “an invention was a musical figure articulated to the point where it could sustain further development,” Elie explains in Reinventing Bach. “In a sense, every new rendering of a Bach work is a further development of the music. Some are better than others—more beautiful, more faithful, more expressive, more imaginative; about the boldest of them, the ones who meet Bach’s patterns most persuasively, we can say that through them Bach is reinvented.”

Elie’s entire book is an invention of sorts. The premise of Reinventing Bach is unusual—it’s not a biography nor a series of personal essays nor musical criticism, but rather all of those wrapped into one, centered on the history of the recordings of Bach. The book blooms open with Albert Schweitzer, the humanist who also happened to be a skillful organist and Bach interpreter, in the act of recording the Toccata and Fugue in D Minor.

As the book moves confidently through time, exploring the recordings of Bach music, the recording technology sharpens with each decade. After Albert Schweitzer, four more great musicians come to the fore, some of them more well known to us today than others: Pablo Casals, the Spanish cellist and Franco dissident; Leopold Stokowski, the American conductor and Hollywood innovator; Glenn Gould, the Canadian pianist and Goldberg Variations disciple; and Yo-Yo Ma, the American cellist and classical music advocate. Occasionally in the book, two of the musicians interact, such as when Gould and Stokowski unexpectedly meet on a train platform in Frankfurt, creating a satisfying counterpoint.

Elie spices his scholarship with some funny moments. Mstislav Rostropovich, the cellist, sets up at Checkpoint Charlie after the Berlin Wall is breached, but the master’s tone “is quavery,” Elie says. “Frankly, he is playing out of tune.”

*****

In my adult piano lessons, I remained out of tune with Bach. After Stephen suggested, in lieu of The Well-Tempered Clavier, that I study the Two-Part Inventions, the obedient part of me ordered the sheet music, but when the mailer arrived, I shelved the score next to the piano. This was baby music, I knew, and I was 43 years old, and since I could play Chopin’s “Raindrop Prelude” with its complex four-note chords, I would not descend to the Two-Part Inventions. Years went by, and I broadened my repertoire with Schumann, Debussy, and Beethoven. I learned how to broaden my mind as well, into an open, expansive plain, so that the music rung out inside of me while I played it on the piano. I had learned how to listen. I performed in concerts with a Manhattan piano society and in recital at Carnegie Hall. Yet the absence in my repertoire of The Well-Tempered Clavier, in fact of any Bach music whatsoever, gnawed at me.

*****

In Reinventing Bach, the historical figure of Bach is anything but absent; in this beautiful tapestry of a book, the passages about Bach’s life are made from threads with a lustrous sheen. The young Bach, recently orphaned at 10, secretly copies out sheet music on moonlit nights. Later, as a father, Bach gives his eldest son, Wilhelm, on the occasion of the boy’s ninth birthday, a practice book that contains the Two-Part Inventions, along with blank pages for father-son compositions, “allowing that the son, like the music in the book, would develop in ways that his father could foresee but could not singlehandedly bring about.” Still later, when Bach publishes his first Partita, he offers the music, in his “curvaceous script,” to “music lovers, to refresh their spirits,” revealing the playful side of his personality.

*****

Towards the end of Reinventing Bach, the news that Bach was going blind moved me to tears. I had come to rely on Bach popping up every 30 pages or so, with his dogged productivity, ethereal music, and tragic and yet blessed family life. And too, I had savored the gifted musicians who interpreted Bach and the innovative leaps in recording technology, along with Elie’s brilliant musings on the relationship of music and time. Then the book gathered speed. Elie listened to the St. Matthew Passion on a train down south, Bach died, and technology reached its current apex, the recordings clustering like grapes on iTunes.

The book was over, and I closed the cover with a feeling of deep satisfaction but also regret. Perhaps I could detain Bach for a while by listening to recordings by the musicians Elie had sprung to life, yet I knew that I really had only one choice.

Late one night, I pulled out the Two-Part Inventions and propped open the book on my grand piano’s music stand. I would start with the first invention, the one in C major, perhaps the first piece that Wilhelm had gazed upon centuries before. I sight-read the treble line, and the music came easily to me. Having read Reinventing Bach, I was ready for this and would not be fooled. The trick would be in how I would interpret this music, how I would hear the two voices, the two singing melodies intertwining in my mind, the personal invention I would make with these Inventions.

Reinventing Bach is available at the Seminary Co-op Bookstore, as well as Amazon.

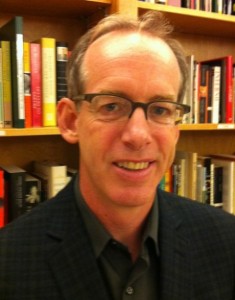

Paul Elie is the author of The Life You Save May Be Your Own (FSG, 2003), which was awarded the PEN/Martha Albrand Award for First Nonfiction, among other prizes, and was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award in biography. Born in 1965 and educated at Fordham and Columbia universities, he worked for many years as a senior editor at Farrar, Straus and Giroux and taught in Columbia’s graduate writing program. He is now a senior fellow with Georgetown University, based in the Berkley Center for Religion, Peace, and World Affairs.

0 Comments